Above the Waves, Beyond the Runway: China's New Ekranoplan and the Littoral Mobility Equation

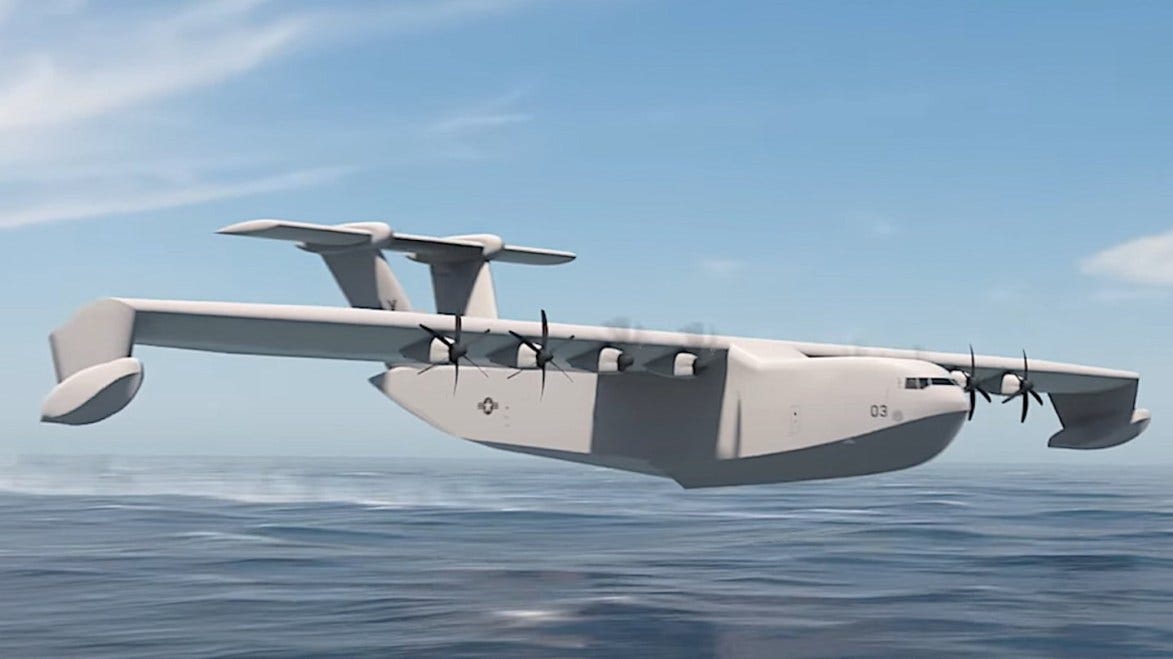

A recent video circulating on Chinese social media has captured defense analysts’ attention: a large, grey-painted, four-jet ekranoplan skimming across coastal waters—its unusual proportions recalling the Soviet Union’s experimental efforts of the late Cold War. While some have rushed to characterize the craft as a “sea monster” or Cold War relic reborn, a more careful reading is warranted. This is not a resurrection of Soviet strike fantasies, nor a clear-cut addition to the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) order of battle. Rather, it may represent something more nuanced—and more forward-looking: an experiment in operational agility within contested maritime zones, one that blends civilian, logistical, and military-adjacent roles.

As always with Chinese aviation prototypes, what matters is not just what the platform is, but what problem it might be trying to solve.

The Operational Appeal of Ground Effect

Ekranoplans—also called ground effect vehicles (GEVs)—fly within a few meters of the sea surface, taking advantage of the ground effect phenomenon: a cushion of compressed air trapped beneath the wing that significantly boosts lift and reduces drag. The Soviets explored these platforms for high-speed strike and transport applications, but technical challenges, vulnerability to weather, and operational inflexibility consigned them to niche roles.

China’s newly observed prototype—large, jet-powered, and seaborne—appears to be the first of its scale in decades. Though details remain scarce, its dimensions and four-engine configuration suggest a transport or logistical role, rather than a weapons platform. This aligns with the broader global trend: DARPA’s Liberty Lifter, REGENT’s coastal transport “seaglider,” and others are all examples of renewed interest in this space—not for strikes, but for mobility in contested or infrastructure-poor environments.

A Brief History of China’s Ground Effect Research

While the Soviets garnered most of the world’s attention in the 1960s and ’70s with their monumental ekranoplans, China was not idle in exploring similar concepts. During the latter half of the 1970s, Chinese engineers under state-led aeronautical bureaus developed several experimental ground effect vehicles, including small-scale maritime transporters and wing-in-ground effect boats for potential use along riverine and coastal zones. These programs were reportedly modest in scope and rarely advanced beyond the prototype stage, owing to technological limitations and the country's broader prioritization of conventional naval and aviation systems during its early reform period.

Nevertheless, the idea endured. In the decades that followed, Chinese state universities and defense-industrial institutes sporadically revisited the GEV concept in academic and engineering circles. What makes the present development noteworthy is that it appears to be the first high-displacement GEV demonstrator produced at a major naval industrial complex—suggesting institutional backing far beyond the laboratory.

That legacy complements the emergence of other large seaplane projects, particularly the AVIC AG600 “Kunlong”—currently the world’s largest amphibious aircraft in production. Although marketed primarily for search-and-rescue and firefighting, the AG600 is optimized for China’s southern maritime theater and could serve dual-use logistics or surveillance roles in a crisis. The newly revealed ekranoplan prototype may reflect a parallel logic: large-scale seaborne transport, without reliance on traditional infrastructure.

Vulnerable, But Contextually Useful

There are good reasons why ekranoplans never became mainstream. They are vulnerable to modern radar, especially from airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) platforms equipped with look-down capability. They are large, non-stealthy, and minimally maneuverable. If spotted by a modern fighter equipped with air-to-air missiles—even short-range IR-guided weapons—they would be relatively easy to destroy. In that sense, they combine many of the survivability weaknesses of both aircraft and ships, without the full advantages of either.

However, those criticisms miss the point. China is unlikely to field these vehicles for deep-penetration combat or strike missions. Instead, this platform should be viewed through the lens of logistics under denial.

Runway Independence: One of the most compelling use cases for such a vehicle is its ability to deliver heavy cargo and personnel to remote outposts without requiring a functioning airstrip. This has obvious implications for operations in the South China Sea or East China Sea, where artificial islands, shoals, and reefs are vulnerable to long-range precision strikes.

Speed over Surface Assets: Compared to PLAN amphibious ships or civilian transports, a jet-powered ekranoplan could reach speeds of 400–500 km/h, reducing the time in which it’s exposed and compressing logistical timelines dramatically. It wouldn’t need to loiter near hostile shores—only arrive, offload, and depart.

Littoral Contingencies: If Beijing envisions a future where islands outposts like Fiery Cross Reef or Woody Island face interdiction, then non-traditional delivery mechanisms like these offer options when conventional air or naval lines of communication are compromised.

Fragility in the Face of Sea State

The most significant limitation to ekranoplan viability remains weather and sea state. Unlike ships, they cannot simply ride out a storm. And unlike aircraft, they cannot always fly above it. The South China Sea is notorious for rough seasonal seas, and even swells over 3–4 meters can jeopardize lift and airframe integrity. Soviet designers struggled with this problem in the 1970s, and it remains a major constraint today.

Modern engines and materials may improve out-of-ground-effect flight capability, allowing for short bursts above storm conditions, albeit at the cost of fuel efficiency. However, any viable doctrine for these craft will need to be tightly integrated with high-resolution meteorological forecasting and sea-state modeling. Their utility may be restricted to fair-weather windows, or post-storm humanitarian missions, where infrastructure is damaged and speed is essential.

Dual-Use Design Philosophy

The appearance of this ekranoplan, painted in a uniform grey but lacking any visible armament, may suggest a dual-use intent. This fits a well-established pattern in Chinese aerospace development. China frequently builds platforms that operate in both civilian and military-adjacent roles—firefighting one day, strategic resupply the next.

In this case, an ekranoplan could support humanitarian aid, disaster response, or commercial cargo logistics, while also retaining the capacity to serve military objectives during a contingency. Beijing’s growing emphasis on “military-civil fusion” makes such flexible platforms increasingly attractive.

Strategic Implications and the Path Ahead

This prototype likely remains a testbed. It is far from a fielded weapon system or even a confirmed production program. But that should not diminish its significance.

What this ekranoplan reveals is that China’s defense-industrial base is continuing its pattern of speculative, forward-leaning prototyping. Not all of these efforts yield operational fruit—but they represent a culture of exploration, something akin to DARPA’s role in the U.S. innovation ecosystem.

It also speaks to a broader trend: the search for infrastructure-independent mobility in the littorals. As airfields and naval bases become increasingly vulnerable to long-range precision fires, new forms of logistics—mobile, fast, semi-aerial—will matter more.

The ekranoplan is not a solution to China’s operational problems, but it may be a stepping stone toward one.

Editor’s Note: the following op-ed draws on a mix of articles, multimedia, and forums I follow, with sources cited accordingly. All opinions expressed are solely my own and do not represent the views of anyone else.