Where Was the Navy on Juneteenth?

As freedom came ashore in Galveston, the U.S. Navy remained offshore—chasing smugglers, enforcing blockades, and fading into postwar obscurity.

On June 19, 1865, the U.S. Navy was not in Galveston Bay in force. By then, its ironclads and gunboats had already swept westward, past the battle flags and fire-eaters, into the murky logistics of postwar occupation and postbellum reality. Galveston saw Union soldiers, not sailors. It was boots, not bluejackets, that brought General Order No. 3 ashore. The Navy’s war had already ended—not with fanfare, but with a file clerk’s nod and a quartermaster’s ledger.

Juneteenth, now a national symbol of delayed liberation, happened in the long tail of the war. But by then, the Navy was in a different fight.

Suppressing the Last Breath

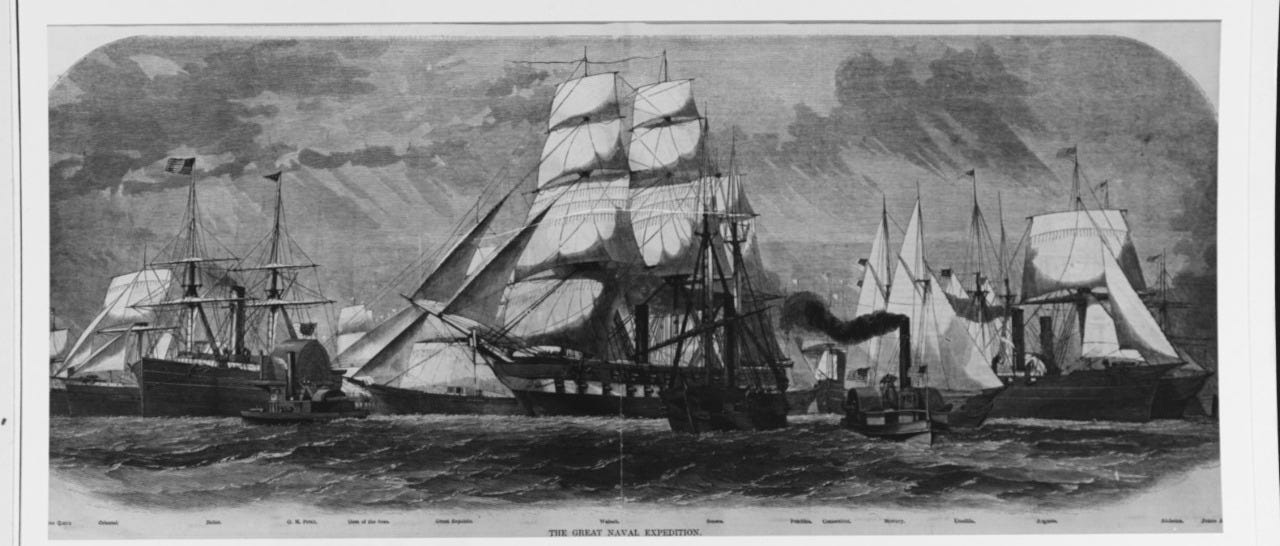

In June 1865, the U.S. Navy was still sweeping the Gulf Coast, chasing the dying embers of Confederate commerce. Smugglers, blockade runners, and ex-Confederate officers were attempting to slip cotton through ports like Matamoros, Havana, and British-controlled Nassau. Though the Confederate government had collapsed, its trade infrastructure lived on—feral, scattered, but profitable. Naval officers were still intercepting blockade runners and seizing contraband vessels even after Appomattox.

The West Gulf Blockading Squadron, once under Admiral David Farragut, remained active along the Texas coast. Ships such as USS Octorara, USS Galena, and USS Metacomet kept pressure on Confederate-aligned sea lanes and neutral ports sympathetic to the South. Matamoros, just across from Brownsville, Texas, served as a key smuggling node—shielded from federal enforcement by Mexican sovereignty, yet vital to Confederate economic survival.

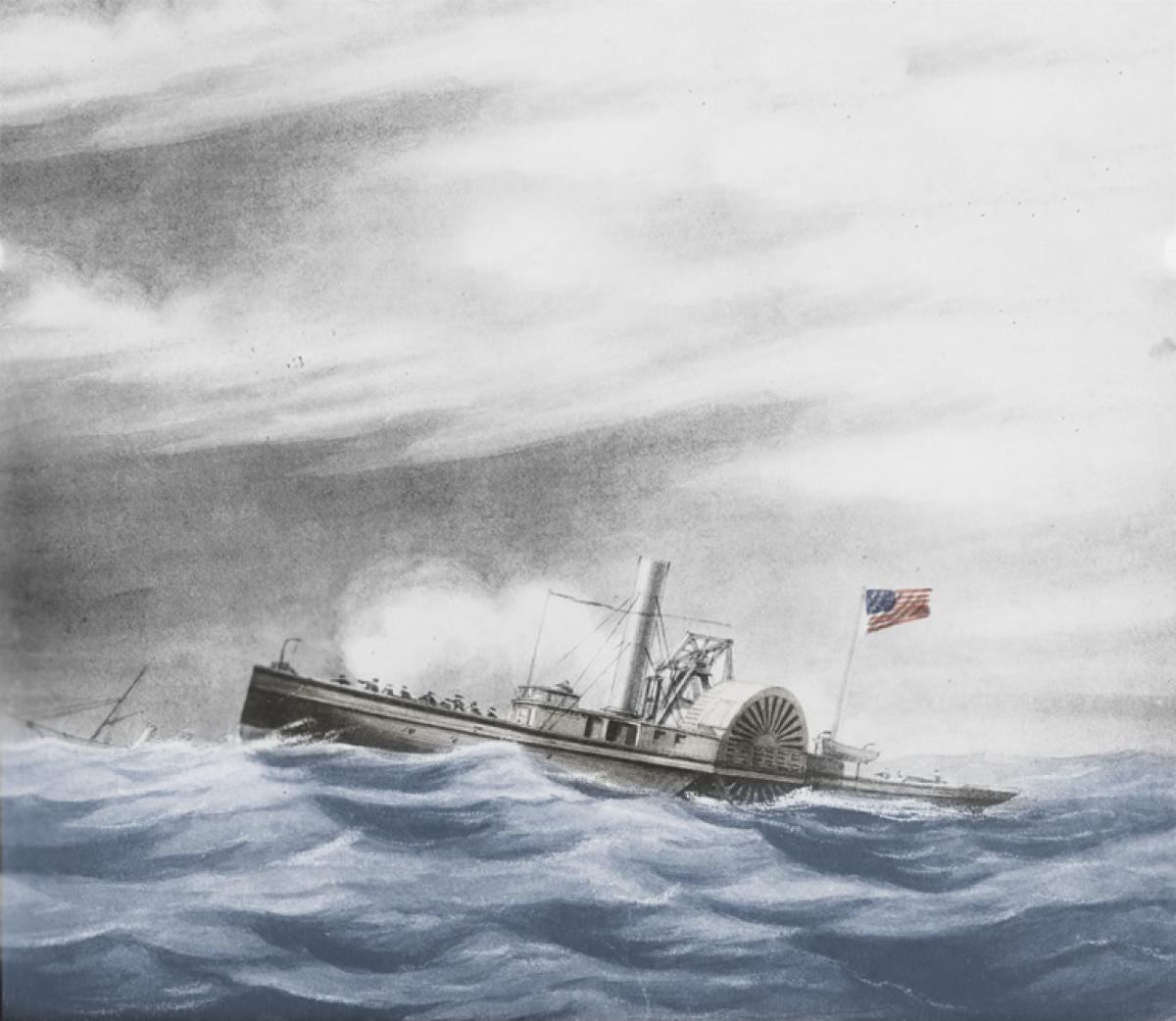

The Navy continued efforts to neutralize Confederate commerce raiders like the CSS Shenandoah, which attacked Union merchant ships. The Shenandoah surrendered in November 1865, one of the last Confederate units to do so.

While the Army occupied cities, the Navy controlled the waters. They weren’t there to liberate. They were there to enforce the developing status quo.

Drawdown and Drift

At the height of the war, the U.S. Navy exploded from a pre-war force of just 90 ships to over 670 vessels by 1865. But that force was already shrinking. Demobilization began rapidly in May and June of that year. With the war over, Congress terminated most naval contracts, and the fleet shrunk to a shadow of its former self.

By 1869, only 52 active ships and fewer than 8,000 personnel remained. The industrial shipbuilding base collapsed. Shipyards along the East Coast laid off thousands. The Navy Department mothballed vessels or sold them for scrap. The postwar drawdown wasn’t part of any grand strategy. It was a fiscal correction.

Even sailors who had helped win the war—including Black sailors—found themselves discharged, unrecognized, and unwelcome in the peacetime order they helped secure.

Beyond Galveston

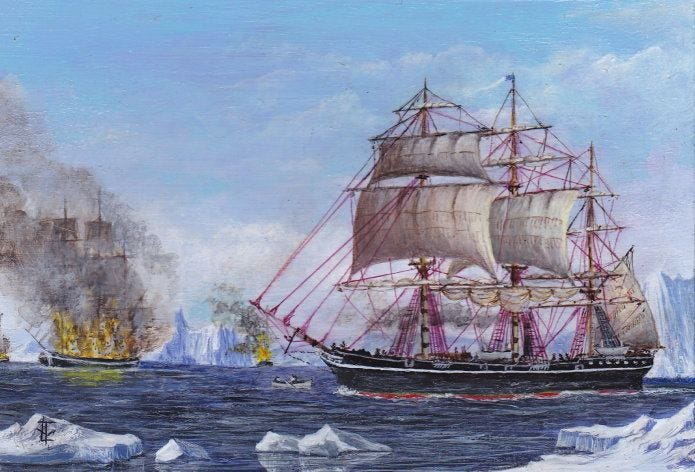

It’s easy to assume Juneteenth marked a new beginning, but for the Navy, it was the afterword to a war it had fought since 1861. From the outset of the blockade, Navy vessels became floating sanctuaries. Escaped slaves who reached federal ships were often taken aboard, provided protection, and sometimes employed as laborers or enlisted outright.

In 1862, the U.S. Navy captured Port Royal, South Carolina, and turned it into a base of operations. What followed became the Port Royal Experiment, an early and imperfect model of Reconstruction. Thousands of formerly enslaved people worked with naval engineers, government officials, and missionaries to establish farms, schools, and local governance.

Black sailors made up nearly 20% of the Union Navy by war’s end—an integration level the Army didn’t match until the next century. These sailors manned guns, piloted ships, and fought in engagements from Mobile Bay to Fort Fisher. But Juneteenth did not honor them. No admiral gave a speech. The Navy remained offshore—its contributions implicit, not ceremonial in nature.

The Sea After Slavery

By the summer of 1865, the Navy had done its part. It had seized the Mississippi, broken the Gulf Coast’s defenses, and isolated the Confederacy’s foreign trade. Now it was slipping into obscurity—still hunting smugglers, still manning blockades, but without the moral momentum that animated the war years.

The sea, after all, has no memory. No battlefield markers float off Matagorda Bay. No bronze plaques stand in the silted harbors of blockade runners. The legacy of the Navy’s role in emancipation was logistical, not mythic. It enforced economic attrition. It gave chase. It denied sanctuary to those who sought to make slavery profitable again.

On Juneteenth, the Navy was still afloat—but already diminishing in strength.

Conclusion

The U.S. Navy didn’t land at Galveston. But it was there in the shadows of the moment. It had helped win the war from the surf and the rivers, by pressure rather than proclamation. Juneteenth—as a military event—belongs to the Army, to General Granger, and to the newly freed. But its shadow was shaped by warships, embargoes, and months of coastal attrition.

On June 19, 1865, the fleet was still out there—chasing smugglers, escorting transport ships, and waiting for final orders.

Not absent.

Just offshore.

Editor’s Note: the following op-ed draws on a mix of articles, multimedia, and forums I follow, with sources cited accordingly. All opinions expressed are solely my own and do not represent the views of anyone else.